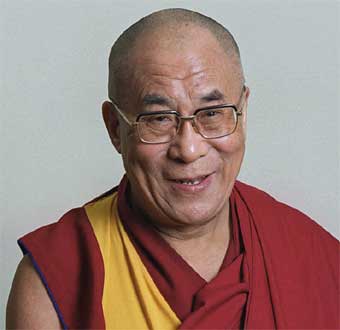

Minds, Brains, and the Dalai Lama.

Colin McGinn, The Mysterious Flame: Conscious Minds in a Material World (New York: Basic Books, 1999), $24.00.

Some scientists are upset that the Dalai Lama has been invited to speak next month to a gathering of neurologists in Washington, D.C. Why would neurologists wish to hear from the Dalai Lama?

Neurobiologists have researched the phenomenon of "brain state alterations" among meditating Buddhist monks and report bizarre findings. Rather than the brain causing changes in mental experience, it appears that mental or spiritual experiences -- choices -- can produce changes in the neurochemistry of the brain. This research suggests that the mind/brain relation is much more complex and reciprocal than we have ever thought. Probably no simplistic, materialistic reductivism will be satisfactory as an explanation of the phenomenon of human consciousness or its effects. This is especially true in a time when the physical world is less physical than it used to be, meaning material reality is recognized as much more dynamic and undefined than it seemed to, say, Issac Newton.

By making the choice to meditate, these Buddhist monks can bring about, voluntarily, drastic neurochemical alterations in their brain-states, according to Dr. Richard Davidson of the University of Wisconsin at Madison, "... the increased levels of neural activity in the left anterior temporal region of the brain [occurred] after persons [took] a course in meditation." New York Times, October 19, 2005, at p. A14.

It appears that the mind can affect the brain directly. Furthermore, this work suggests that there is a connection between spirituality and ethical behavior -- behavior which is socially beneficial. Persons who are able to produce, through will power, these changes in themselves become more happy and compassionate people in society. Enlightenment leads to goodness.

"The control of mind over matter is startlingly illustrated by recent research by a team at Stanford University Medical School. A study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science described how patients using high tech imaging equipment were able to focus on their brains and control activity in one of their pain centers through mental exercises. Dr. Sean Mackey, co-author of the study, claimed the ability to control chronic pain in this way, with practice, 'could change people's lives.' ..." Philosophy Now, February/March 2006, at p. 6.

The serpent in this garden is Dr. Nancy Hayes, a neurobiologist at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Jersey. (It had to be New Jersey.) Dr. Hayes finds such research dismaying to her own view of things and wishes to prevent the Dalai Lama from speaking to the scientists because, she claims, talk of spirituality makes "us the equivalent of the flat earth society."

Let me see if I can figure out this person's problem: 1) She dislikes spirituality because it is "irrational" in her judgment, so she is concerned that 2) religion not be confused with science -- since science is what highly rational and educated people, such as herself, happen to respect.

Being an atheist or agnostic, a Darwinist (I "believe" in evolution), and an advocate of science -- when it comes to the investigation of nature -- may help to soften the blow when I say that Dr. Hayes is mistaken. Science does not have an exclusive on all forms of intellectual inquiry. Moral, aesthetic, political and many other questions will never be answered by conducting an experiment. Furthermore, there are some phenomena -- including the mysteries of mind/brain relations and the reality of human spiritual experiences, which are quite natural by the way -- that are amenable to study by scientists and humanists for different purposes, with different objectives in mind, in different ways, all at the same time. The results of these studies may enrich one another.

Fortunately for science and the First Amendment, research into these fascinating phenomena continues and the Dalai Lama will speak to the scientists after all. Dr. Carol Barnes, President of the Neuroscience Society of America, refused to cancel the talk by the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism and, wisely, she wishes to encourage this research.

In a second fascinating article by Laurie Goldstein, "Witness Defends Broad Definition of Science," The New York Times, October 19, 2005, at p. A15, Dr. Michael J. Behe, of Lehigh University, defended the increasingly popular theory of "intelligent design" -- which is not the same as "creationism." According to intelligent design theory (which I do not accept) "random natural selection" in Darwinian evolution is rejected in favor of intelligence or "rational pattern" as an explanation of genetic alteration.

By focusing on patterns of rationality or intelligence in nature, some scientists hope to explain how "complex biological structures arose." These theories are distinct from, but compatible with, holistic accounts in physics that explain reality in terms of an "implicate order" (Bohm) or "emergent phenomena" (Capra). In summarizing an earlier phenomenological argument against a simplistic mind/brain identity theory that says that mind is reducible to the "brain thinking," Professor Colin McGinn says:

Suppose I know everything about your brain of a neural kind: I know its anatomy, its chemical ingredients, the pattern of electrical activity in its various segments. I even know the position of every atom and its subatomic structure. I know everything that the materialist says your mind is. Do I thereby know everything about your mind? It certainly seems not. On the contrary, I know nothing about your mind. I know nothing about which conscious states you are in -- whether you are morose or manic, for example -- and what these states feel like to you. So knowledge of your brain does not give me knowledge of your mind. How then can the two be said to be identical?

No account of mind/brain relations that is false to the rich, technicolor phenomenology of being a conscious agent -- a freedom in the world -- will be persuasive in the long run.

I know what it feels like to love a woman. "Neurons firing" is not exactly the first description of the experience that comes to mind. To be sure, we are animals with fancy brains, but part of the mystery of those brains is their inexplicable capacity to produce consciousness and all that comes with consciousness -- not only the capacity to create a Ninth Symphony or a Sistine Chapel, but also the ability to appreciate such works, or something as seemingly ordinary as humor, a smile, or a wink as opposed to a blink. (See "Has science made philosophy obsolete?")

Back to the laboratory folks. Incidentally, you may wish to take a philosophy course before you return to your research.

Labels: Consciousness, Minds, Spirituality.

<< Home