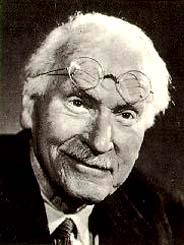

Carl Jung on Selves and Shadows.

This essay has been "noted" at: "Beauty, Anxiety, Selves and Shadows," http://www.fidotheyak@blogspot.com/ I also have "reason to believe" that my book is listed by "best book buys": Juan GalisMenendez, Paul Ricoeur and the Hermeneutics of Freedom (North Carolina: Lulu Press, 2004) and http://www.lulu.com/JuanG and http://www.bestwebbuuys.com/ ; see also http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/141160413X/002-4045201-9063230?v=glance&n=283155

Whatever comes from weakness is evil.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Ambiguity, if not mystery, best characterizes most of us, who are neither St. Francis of Assissi nor Charles Manson, fortunately, but who live between these extremes that define the ultimate human alternatives. We all have an interest in being aware of what those extreme options are, even if most of us will never embrace either of them. It is vital to appreciate that all human actions exist on a moral scale that includes the full spectrum of human possibilities. For each person all things are possible, true, though some things are far more possible for one person than another. There is always an element of good fortune when a person receives the support and love that allows him or her to choose wisely, to opt for love and not hate, to decide that there are some things that he or she will not do, no matter what.

This humbling recognition of one's limits comes with the understanding that those who engage in the worst acts may not have had one's opportunities and advantages in life. It should lead us to feel compassion for human frailty without undermining our unwavering commitment to ethical ideals, even as we recognize that we will never fully achieve our own ethical ideals. The important point to understand is that this does not invalidate the ideals.

It appears that the "gift" of freedom -- that apple that Eve was tempted to give to Adam, or was it the other way around? -- is ambiguous. Free human beings will either violate one another in some ways, or they will love one another. W.H. Auden suggested that we must love one another or we shall die. Neutrality is not likely to be a final option in the development of any human personality because directedness towards one alternative or the other -- as opposed to actually achieving absolute goodness or evil, which may not be humanly possible -- cannot be avoided. Everyone must choose either to walk towards the light or the darkness, while recognizing the equal inclination to both in one's flawed human nature.

Pascal said somewhere that "whoever seeks to be an angel will be a beast." What we must not deny is the reality of the options for all of us. The sad truth is that each option is attractive on occasion. Only nihilism and apathy are, as they used to say in the sixties, the ultimate "cop out." How closely intertwined are feelings of love and hatred, of good and evil? Carl Jung suggested that "Jesus and Satan are brothers." What did he mean by this?

"None of us stands outside of humanity's black collective shadow," writes Jung, "Whether the crime lies many generations back or happens today, it remains a symptom of a disposition that remains always and everywhere present -- and one would do well therefore to possess some imagination in evil[.]"

The Undiscovered Self (New York: Penguin, 1957), pp. 108-109.

Jung goes on to say:

"Here we come up against one of the main prejudices of the Christian tradition, and one that is a great stumbling block to our policies. We should, so we are told, [avoid] evil and, if possible, neither touch nor mention it. For evil is also the thing of ill omen, that which is tabooed and feared. This attitude toward evil, and the apparent circumventing of it, flatter the primitive tendency in us to shut our eyes to evil and drive it over some frontier or other ... [During a time filled with commerations of the Holocaust, the point bears re-emphasizing:] But if one can no longer avoid the realization that evil, without man's ever having chosen it, is lodged in human nature itself, then it bestrides the psychological stage as the equal and opposite partner of good. This realization leads straight to a psychological dualism, already unconsciously prefigured in the political world schism and in [the] even more unconscious dissociation in modern man himself."

The Undiscovered Self, pp. 109-110 (emphasis added). See also, Ronald Hayman's chapter entitled "Jesus and Satan Are Brothers," in A Life of Jung (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999), pp. 402-418.

In what follows, I wish to say something of what Jung might have been concerned to demonstrate about human nature. Goodness and evil exist as possibilities for every human being with the capacity for moral freedom, so that the goodness which results from love must be chosen, and more than once, by every individual. The worst thing to do is to ignore or repress the "shadow-side" of the self, however, because it may then be projected out towards others, until it explodes from the dark corners of the psyche.

Choice is what makes moral alternatives meaningful. In the absence of choice -- with CONDITIONING, for example -- a person is no longer a person, so that good and evil, love and hate are no longer meaningful terms. Persons "behaving" under conditioned responses, for instance, become mere objects, incapable of agency, until they choose to rebel and select their own meanings for those conditioned responses, in order to regain their humanity.

Nothing that is done to, or by, a person in a state of mental helplessness is attributable to him or her, but it will always be for the individual to decide later "what to make of what is made of him or her" (Sartre) in such a state of helplessness. From any humane or ethical perspective, such a thing -- the turning of a human being into a "meat puppet" -- is ultimate evil and can never last for very long.

It is important to bear in mind the simultaneous proximity and distance between these opposite ends of the moral spectrum. To choose is at least to be human. To be deprived of choice is true evil, for it amounts to being deprived of one's humanity. Any behaviorists out there should memorize this next phrase: You cannot force emotions, value-judgments, or understandings of life down a person's throat. You cannot and must not presume to "fix" people. Norman Mailer writes in a Jungian spirit when he comments of his early essay collection:

"It is a good fit -- The Saint and the Psychopath. Because these are writings on two themes, violence and the mystical, writings about what is criminal and what is religious, and the root of my perception all those years ago ... that the saint and the psychopath were united to one another, and different from the mass of men. They were closer to existence. They shared a sense of the present so powerful that memory, caution, precendent, tradition, commonplace, project, and future enterprise were nevertheless before the sense of the present in their mind and body. In their most incandescent states, they existed for their next breath, and so were indistinguishable from one another; saint and psychopath -- a murderer in the moment of his murder could feel a sense of beauty [I have a different view than Mailer of the role of beauty] and perfection as complete as the transport of the saint. (And indeed this was the root of the paradox which had driven Kierkegaard near to mad for he had the courage to see that his criminal impulses were also his most religious.)"

Existential Errands (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1972), p. 210.

Compare this quotation from Carl Jung:

"We cannot change anything unless we accept it. Condemnation does not liberate, it oppresses. ... If a doctor wishes to help a human being he must be able to accept him as he is. And he can do this only when he has seen and accepted himself as he is. Perhaps this sounds very simple, but simple things are always the most difficult. In actual life it requires the greatest art to be simple, and so acceptance of oneself is the essence of the moral problem and the acid test of one's whole outlook on life. That I feed the beggar, that I forgive an insult, that I love my enemy in the name of Christ -- all these are undoubtedly great virtues. What I do unto the least of my brethren, that I do unto Christ. But what if I should discover that the least amongst them all, the poorest of all beggars, the most impudent of all offenders, yea the very fiend himself -- that these are within me, and that I myself stand in need of the alms of my own kindness, that I myself am the enemy who must be loved -- what then? ... Had it been God himself who drew near to us in this despicable form, we should have denied him a thousand times before a single cock had crowed."

Psychology and Religion: East and West (New York: Pantheon, 1958), p. 339. ("Pieta.")

Much as I love the United States, it must be said that there is a bizarre celebration of violence in contemporary American culture. This is evident even from some of what is best about us, for instance, from the energy in Hollywood cinema, especially in action films and pop music. Just think of anything by Quentin Tarantino, whose work I generally admire. Gangster films, Westerns and shoot 'em ups of all sorts are often characterized by an obscene delight in gore and the depiction of suffering. This is true, as I say, in all categories of contemporary Hollywood movies -- even in the Matrix films (which I like) there is too much fascination with guns and beating people up, along with a very healthy focus on the tight leather outfits worn by some of the protagonists.

There are two aspects to this love affair with violence and flirtation with evil -- a dangerous flirtation which should be avoided at all costs -- that I wish to examine in my comments here: 1) the agent's quest for "authenticity" and how it is affected by the ever-present threat of violence; and 2) the agent's joy and need for a "will to power" over others. See Michel Foucault, ed., "I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, my brother" ... A Case of Parricide in the 19th Century (New York: Random House, 1975), pp. 208-209.

My entry into the discussion is Norman Mailer's weird and intriguing remark, which does not reflect my view and which was made after Mailer's arrest for stabbing his then wife, Adele: "Murder is always a sexual act." I am interested in Mailer's statement, even though he did not, in fact, murder his wife, because I think that it captures an important insight that may be associated with some of the writings of diverse thinkers such as Nietzsche, Adler and Foucault, while fitting in to the Jungian picture of duality in the human psyche.

Alfred Adler (and before him Friedrich Nietzsche) spoke of the fundamental importance of the will to power. Foucault was obsessed by the pervasiveness of power, even in his late discussions of the "technologies of the self" engaged in the process of creating an identity. There is an erotic charge (for some people) in wielding power over others (Diana?), so it should not surprise us at this late date in history -- think of what the twentieth century was about! -- that many life-long criminals (and serial killers especially) report that they experience orgasms when holding life or death power over others. (Diana? Terry?) Much the same is true of torturers (George Orwell says: "the purpose of torture is torture") inflicting suffering on victims. Now that is what I call "sick." (See "Terry Tuchin, Diana Lisa Riccioli, and New Jersey's Agency of Torture" and "What is it like to be tortured?")

Typically, such highly disturbed individuals experience fantasies of supernatural power, even naming themselves for mythological characters, usually demonic ones, in a twisted "Silence of the Lambs" fashion. Rather than adopting a humble Internet alter-ego, for instance (something like "Fred" or "Friedrich"), they opt for names like "Malbus" or "Mephistopheles," or something sinister like that. Almost all torturers come to aquire these characteristics and tendencies.

Is it a coincidence that Foucault was enthralled by sado-masochistic sexual performances? I wonder about some of the connections between the darker aspects of the philosopher's life and his scholarly work, so does Foucault's biographer James H. Miller. I suspect that Jung would not have been surprised by this feature of Foucault's personality, given the subject-matter of the French theorist's books. In particular I am reminded of the first pages of Discipline and Punish, depicting the torture and killing of Damiens. There is a bit of the sadist in many judges or therapists and other wielders of power. (See "A Killing in New Jersey's House of Healing.")

When a group of people is asked by a strange man in sandals, "Who will cast the first stone at the adulteress and sexual outlaw?" Beware of the person who rushes to accept the invitation because it is "for her own good." (See my essay on Ayn Rand's philosophy and the link at the Objectivism Research Center, at: http://www.noblesoul.com/orc/books/rand/pwi.html .)

Yet a more important reason for some people's need for that violence which most of us find repugnant, is the desperate effort to escape boredom -- boredom afflicts the wealthy as much as the poor, especially young people, which explains the "affectless" reactions of the youthful criminals who shot their classmates and vandalized their school in a sleepy, "all-American" mid-west setting recently, seemingly for no apparent reason. It may go a long way towards explaining the smiles on the faces of soldiers serving as torturers at Abu Ghraib. You getting this, Terry?

Violence has become so prevalent and comfortably unreal, in a computer game-like sense, that it almost makes no difference to the "perpetrators" either to kill strangers at a school or at a mall in the morning, or to go for a pizza in the afternoon. Soon, perhaps, even homicidal acts will become boring also for the hyperstimulated, while we old-fashioned types are still thrilled at the thought of a cup of tea and the collected stories of Sherlock Holmes. The kids will yawn as they "pillage and burn" before dinner, then pop I Know What You Did Last Summer -- or worse, Donnie Darko -- into the DVD player.

What is sad or even tragic is that this may only represent one way, a final way maybe, for such people to obtain a genuine emotional response from others. Violence may be a strange atttempt to elicit a bit of attention and, bizarre as it seems, a way of asking for love. It is better to affect a person in some fashion, usually a person who is secretly desired as a sort of trophy or object of control, than not at all.

"When inward life dries up, when feeling decreases and apathy increases, when one cannot affect or even genuinely touch another person, violence flares up as a daimonic necessity for contact, a mad drive forcing touch in the most direct way possible. This is one aspect of the well-known relationship between sexual feelings and crimes of violence. To inflict pain and torture at least proves that one can affect somebody."

Rollo May, Love and Will (New York: W.W. Norton, 1969), p. 30.

At the conclusion of the film Blade Runner, the cyborg slams his hand down on a nail just to feel something, anything. For Sartre, a similar gesture by his literary character was a philosophical demonstration of freedom in his novels, The Roads to Freedom. Sartrean persons say: "I am free because I can choose this painful act." By the late twentieth century, with the arrival of postmodernist culture, the cinematic character's gesture in Blade Runner is a desperate attempt just to feel something, anything, rather than nothing. The gesture becomes a protest against death, but much more it is a final response to death-in-life. What is opposed and rejected is the condition of an Eichmann, a perpetual state of emotional numbing and banality. Most of us will not find it necessary to slam that hand down on a nail, because we experience an equally intense and much more pleasant sensation and spiritual fulfillment, simply by loving others.

Many persons committing desperate acts of violence these days want the rush. They want to experience Andre Gide's acte gratuite. They want to feel the fear and energy that they can produce in others -- which assures them that they are still alive, in a society that increasingly deadens, numbs and diminishes them. I suspect that many of the same feelings will be found to exist in the Abu Ghraib torturers. ("Psychological Torture in the American Legal System.")

High culture has little meaning for violence-prone young people, because they have too often been told that highly regarded cultural objects are "elitist" and not for them, or that all cultural products are of equal value anyway -- or much worse, that all ethical and aesthetic standards are merely "relative," so that there is no ultimate difference between, say, the plays of Shakespeare and Bugs Bunny cartoons. ("Is Humanism Still Possible?")

The advice of William James and John Stuart Mill concerning the therapeutic uses of high culture for the expression or cultivation of emotions and avoidance of violence is ignored. Sensation replaces meaningful cultural experience, the "gee whiz" response replaces the authentic aesthetic moment, sex replaces the much rarer experience of love and of love-making, feeling pleasure is falsely assumed to be all that can be meant by feeling deeply. Being moved by a poem, by a philosophical essay, by music that is centuries old is cause for laughter and ridicule. The result is the vacuity and banality of too many (usually affluent) young people's lives, which can be every bit as devastating for the psyche as the despair experienced by the destitute. ("Nihilists in Disneyworld.")

I have admitted that I am old-fashioned, so my prescription is an old-fashioned one: love and beauty. In order to foster feelings of human solidarity and moral concern, respect for the autonomy of persons and their fundamental emotions must not be ignored or tarnished. I am sure that, through our deepest relationships, we learn best how to recognize the genuineness of another human being's emotions and desires, to give those emotions and desires weight and importance, but also we may come to appreciate the mystery and sigularity of all that is outside of us, through the contemplation of beauty. Love and beauty are ways of transcending our particularity in order to achieve a larger acceptance of, and unity with, others and the world that is external to us.

In a loving and appreciative stance towards all that is outside of us -- especially the persons we revere -- evil becomes an impossiblity. Richard Rorty is helpful on this issue and is, at the same time, someone to learn from in thinking about human solidarity. Professor Rorty is certainly correct to suggest that "cruelty" is the worst thing that human beings are capable of, though how this assertion fits with his skeptical view of ethics is not very clear to me. (Care to deface this essay today?) The quality that is often missing in those capable of great evil, is the ability to empathize with -- or even recognize -- the feelings of others through a recognition of their fundamental equality:

"The traditional philosophical way of spelling out what we mean by 'human solidarity' is to say that there is something within each of us -- our essential humanity -- which resonates to the presence of this same thing in other human beings. [To be inhuman,] is to lack some [crucial] component which is essential to a full-fledged human being."

Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 189.

It is only possible to torture another human being, who is helpless -- as a result of drugging or hypnosis, for example -- if that person's humanity can be denigrated or ignored to such an extent that it becomes non-existent. The torturer enjoys the process of domination, of reducing another person to the status of a "pet monkey," a slave, whose only function is to serve the master. Torture injures its victims, but it also hurts those who do the torturing and who become addicted to the thrill of power over others. It is ironic that by dehumanizing others, a person is instantly, and to the same extent, dehumanized. ("Not One More Victim.")

A torturer's "affective" capacities wither and atrophy, along with sensitivity to the feelings of others or any talent for understanding them, so that the quest for sensation grows increasingly desperate, intense and irrational, and the need to dominate and hurt others becomes overwhelming, with the result that the torturer will always be the one most injured in the end.

The images from Abu Ghraib of some American soldiers torturing prisoners then seem much more understandable, as does the unshakable commitment of U.S. institutions (I hope) to ensuring that torture is never tolerated nor believed compatible with the values of the United States of America, regardless of who is president at any given time. Like the single individual who must confront and overcome -- through a loving transcendence -- the shadow-side of his or her own nature, so it is that all societies must face and cope with the tendency to violence and injustice in human nature, as Jung explains, seeking both to protect against and to understand the mystery of wickedness. ("What is it like to be tortured?")

Labels: and Norman Mailer., Archetypes, Carl Jung, Selves, Shadows

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home