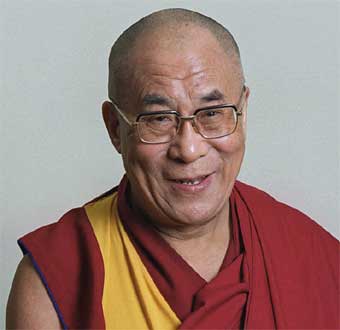

Images -- like the portrait that appears above -- may be blocked at any time by N.J. legally-protected hackers.

Images -- like the portrait that appears above -- may be blocked at any time by N.J. legally-protected hackers.

Adrienne Koch,

Power, Morals, and the Founding Fathers (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1961), $7.95.

The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States (New York: Bantam, 1998), $2.95.

Yesterday I spoke of the need for an articulation of basic values for

us. We contemporary Americans, regardless of race or ethnicity, gender or economic status, need to say what beliefs we share and why. We also must be clear-eyed in describing the less than ideal reality we see all around us. If we are now incapable of articulating a foundational and communal set of values or ideals, then we are no longer a nation or a people, even if we share the same geographical space and purchasing habits.

I think that it

is possible to state such a set of values. I have tried to offer a hint of what those values may be in "Civilization and Terrorism" and "Manifesto for the Unfinished American Revolution."

In trying to define those values, I will say simply that the United States is an experiment. It is a fragile hope that people can govern themselves, in accordance with a set of principles of moral and political philosophy that will require

interpretation by each new generation of Americans, fashioning a structure of government in which power is shared and limited by law.

The purpose of this effort is to guarantee freedom and equality to each citizen as against the power of the State. Given the realities of human nature, this must have seemed a childish dream to the men who drafted the Constitution and put it into practice. Every form of skepticism about whether power can really be limited by law was expressed by the framers. They were not foolish "idealists" or "dreamers." They were not "evil racists," though they were products of their times, limited by the blindness and stupidity of the era in which they lived, while struggling for emancipation from every form of superstition. They were certainly

not creating a revolution in order to get rich. They were rich already. The revolution, along with the creation of this nation, cost most of them a great deal, including the lives of family members and friends, or their own lives in some cases.

The authors of the Constitution were flawed human beings, certainly, but at a time when it was still possible to hold lofty ideals without embarassment and to be optimistic about the possibilities of humanity, they insisted that people might be

made better by good government. Today the use of these words alone results in laughter and dismissals, as I can attest. We are all too cynical for such beliefs in the post-Watergate and post-Monica era. We must return to an appreciation of the foundational values of American society in order to move forward and decide what those values require today.

In a time that celebrated progress and reason -- despite the horrors of war and rigors of life -- there was still a confidence in the future of a free people that is difficult to imagine today. Despite my moments of despair, I share in that confidence about America. Words like freedom, equal protection and due process were designations of values held to be

real and true under the new Constitutional structure. This is because they were and

are real and true. Today, I am often saddened and angered at the laughter with which they are greeted. To use such words means that one is called a "fool" or a "child." If so, then I accept the labels. ("Why I am not an ethical relativist" and "John Finnis and Ethical Cognitivism.")

One meaning of the term "postmodern" is an "incredulity toward all metanarratives." (Lyotard) Another attempt to establish a definition of this intellectual orientation ("postmodernist"), however, comes from theology (Paul Ricoeur) and is concerned with the challenge of hanging on to humanism and the universal in the aftermath of the Holocaust, as a hope for humanity.

By this theological-philosophical understanding, to be "postmoderns" is to find a way of living between contradictions in an effort to resolve them. At least in

one reading or interpretation of Paul Ricoeur's work, this holding on to freedom and humanism -- as embodied in symbols -- is still possible, as a kind of "hermeneutics of freedom" that allows for social justice. Think of a crucifix or other great symbols, so as to decide what

they mean for

us today.

The United States of America is based on a hope that people can live freely. "People" is a word that the framers understood more narrowly than we do now. We have learned -- partly from their own principles -- that freedom and equality means that all or none of us must be "equally" free. And yes, the attempt to achieve freedom with equality is an on-going one. The struggle will never be finished. The American Revolution will never be

only an episode in history books. ("John Rawls and Justice.")

Perhaps our revolution should never be finished or achieved definitively, because there will be new challenges for every generation of Americans posed by the enemies of freedom, who will always be around. These challenges force us to reconsider our commitments to the foundational values that I am describing. Most importantly, we must be on guard not to become, unwittingly, one of those challenges to legality and freedom ourselves, as we surrender to a fashionable cynicism. Be skeptical, by all means, but believe

something. In the immortal words of Ronald Reagan, who is NOT my favorite president: "trust but verify."

Freedom is a scary thing. Many people prefer to be told what to believe or how to behave. They want someone else, an authority figure of some sort, to tell them what is true and what commands to obey. "Most people want to be told what to believe," a torturer once said that to me. If this is true and if you can get away with your crimes by telling people that "it never happened," Terry, then you will not get away with your crimes against me because I

know what happened. Furthermore, I have obtained empirical evidence of these sordid events. ("Terry Tuchin, Diana Lisa Riccioli, and New Jersey's Agency of Torture.")

The American Constitution prevents the government from doing exactly that prescribing of moral opinions. It leaves decisions concerning what gods to believe in, or whether to believe in God at all, what to say, how to dress, what party to vote for, or whether to vote at all -- all of these things and many more (like who to love) are for the individual rights-bearer to determine, without interference from anyone. This is true no matter who that person is, or how much money he or she has, or what political friends he or she may have, or what family the person is born into. ("Is there a gay marriage right?")

The Constitution provides government for grownups. Yet what the Constitution tells us makes us mature (moral intelligence and freedom) are things labelled as "childish" in today's intellectual culture.

The American media that looks chaotic and disrespectful of our leaders to other nations is actually performing exactly the role that the framers envisioned and desired: keeping our governors honest -- or as honest as possible when it comes to politicians -- by preserving a climate in which the free expression of ideas often results in the creation of new ideas.

Attempts to censor or destroy my writings make it clear that such efforts are always endangered. One reason for making movies like, say, "Michael Clayton," "Wall Street," or the Paul Newman classic "The Verdict" is that they are mirrors turned on powerful sectors of American society. Great art always tells us who we are. We do not always approve of the reflections of ourselves on screen.

American irreverence and suspicion of pomposity is one of the greatest aspects of our political culture. Commentators like Al Franken, Jon Stewart, or even the much-dreaded Mr. O'Reilly on Fox -- whatever their politics -- are always good for the nation. I love it that Americans refuse to be impressed by politicians. We tend to revere them only after they have left office, which really pisses them off. We must not forget that such freedom to criticize is what the Constitution protects and makes possible.

No system of government or laws will change the reality of human nature, but in America we can confront institutions and powerful politicians with our professed national values and force them to act, to do the right thing. We can ask that they live up to the values found in the Constitution. In general, they will. If they don't do the right thing, then we get new ones who will. ("Presidential Debates.")

The Constitution is about you. It is about what the

government cannot do to infringe on your rights. You, the citizen, are most important under the vision of the Constitution, especially under the Bill of Rights. Not some abstraction like the State, or the "collectivity," but you. That's right. The guy or gal who gets on the bus, who goes to the Yankee game once in a while, who discusses politics with his friends in the summer time, while playing Dominos on the steps of his or her building.

You are what the Constitution and the legal system are about, ultimately, and you matter more, much more, than ideologies. The State, Constitution, the law are, primarily, instantiated in your relationship with the government and with other citizens.

It is true that rich people and corporations have lobbyists. But then, you also have a lobbyist in Washington, D.C., you've got the best possible lobbyist. The Constitution is your lobbyist. You can show up any time and hold it up for the politicians to see. Don't let them forget that they work for you. It still amazes people who become citizens that they can go and protest in front of the White House. Well, you can. The President may even come out and try to get your vote.

Each time an "error" is inserted in this essay is a further desecration of the documents for which men and women have given their lives in every generation of American history. I consider the continuing ability of minor criminals from New Jersey's corrupt political structure to disgrace American law the most overwhelming evidence of America's decline. If you have children in the United States, this spectacle should frighten you.

This idea of freedom works everywhere in the world. People, individuals with rights, come before the power of the State, which must serve

their interests to be legitimate. How can I believe this, given some of my own experiences in America, and all of the corruption that exists in many jurisdictions?

I believe it because it is what allows me to

protest the injustices that I have experienced and seen (including defacements of this very essay), while criticizing (publicly) practices that I find objectionable. It is still true that there are not many places in the world where this is possible for a single poor person. I am still alive (so far!) after expressing my opinions. Most places in the world, this would not be true. My daily war against censorship should be visible to the American people. This is when New Jersey should try to block my computer's cable signal, again.

Many political leaders from different parts of the world are beginning to accept this premise of inviolable human dignity. This valuing of the individual leads to an ideal of community. It is not a "heartless individualism for greedy capitalists." There is an ethic of community at the heart of the American experiment. I think it is best articulated, at the outset, by Thomas Jefferson and a few others:

Jefferson offered an incisive criticism of ... egoism and took issue with the attitude of Helvetius that self-love is the root of even our seemingly altruistic behavior. [Mr. Posner?]

Jefferson's objections were drawn from his view of [the person]

as a social creature rather than from the isolated individual that some eighteenth-century theorists envisioned.

But HOW can virtue be a guide to the pursuit of happiness? Jefferson's answer here moved beyond the ancient philosophers to the inspiration of Jesus, for he considered that the ancients failed to recognize the reality of love and of duties towards others. Jefferson went to considerable trouble twice in his life to collect "The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth" from the books of the New Testament. He believed it was Jesus who had set the world on a more humane moral level by teaching the "most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has been offered to man."

Notice that Jefferson's point is about a

secular ethics of love leading to liberal or "diverse" political community. This has a lot to do with his choice of the word "happiness," together with "life" and "liberty," in the

Declaration of Independence.

Terrorism is a denial of these beliefs. It reduces persons to objects to be destroyed in order to dramatize a political point. You have to make a decision today, at the most fundamental level, about what you believe and where you stand in this global struggle in which we find ourselves placed by history. The people inserting "errors" into these writings are terrorists.

I know where I stand. And I will continue to try to explain what I believe and why it is important. I have that right under the Constitution. So does George W. Bush. Whoever the next President of the United States will be, he (or she) will agree with Thomas Jefferson on this much:

"I have sworn upon the altar of God, eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man [or woman]."

The life of reason involves the free use of mind or body -- it is the life fitting for man [or woman,]

in view of the natural capacities of human nature.

George Santayana was so moved by this text that his systematic philosophical theory in four volumes was entitled: "The Life of Reason." ("An Open Letter to My Torturers in New Jersey, Terry Tuchin and Diana Lisa Riccioli" then "Is America's Legal Ethics a Lie?" and "America's Torture Lawyers.")

Americans will not allow anyone to deny us these rights to life as reasonable and dignified persons. ("Is there a gay marriage right?")

No one will threaten us into abandoning our rights nor prevent us, as individuals and (I hope) as a government, from advocating the same rights for ALL other persons, wherever they may be and whatever their condition in this world.

Labels: Caritas, Politics., Thomas Jefferson